Matching a Face to a Name: The Potential of Images and Legacies

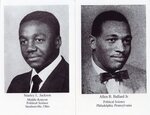

This week in the archives, we were given the opportunity to match faces with the names of those that we've been studying as having been made part of acts of inclusion or intentional exclusion. By exploring the "Person Files," we found key figures that acted as trailblazers in Kenyon's progression to a more inclusive and informed college. My folder held information about Stanley L. Jackson, or "Speedy Stan" which was scrawled atop the folder next to his legal name. He was one of the first Black students at Kenyon, alongside Allen B. Ballard Jr., both of whom were featured in the document we had found earlier recounting the history of the Men of Color at Kenyon organization. Their even attending Kenyon was an intent-filled act of inclusion and integration, though it was certainly rocky at times, as there was a scandal surrounding a football game at Sewanee being cancelled due to the coach at Sewanee requesting that the two Black players didn't play. The cancellation of the game reflected a sense of unity among the players, but I'm sure that the two students' time at Kenyon was fraught with more exclusion than just a single game.

"Allen B. Ballard, Jr. and Stanley L. Jackson become the first African American graduates of the College since William J. Alston's graduation from Bexley Seminary in 1859." (Digital Kenyon)

Being able to match these faces to the names typed out into the archives of Kenyon was a powerful experience. Much like the Aristotelian ideas of pathos, ethos, and logos, it's pertinent to our portrayal of the past that we include factors that tug on the heartstrings of the audience, appealing to their pathos. This can be used both as we convey and derive meaning from the past as well as a strategy of movements of inclusion. Of course, as Yazdiha explores how social movements strategize and contextualize with the past, she explores of similar ideas through her imagery of the "gnarled branches of civil rights memory" (pg. 47, The Struggle for the People's King). There are just about endless ways of going about interpreting the legacy of an iconic figure like King or an iconic event like the integration of the college. It's nearly impossible to separate these interpretations from their larger causes or movements.

Yazdiha also explores how colliding movements have warped and distorted the image of King to suit their own means and motivations. One almost ridiculous example of this was how King's image was juxtaposed with an image of two men kissing and captioned "Martin Luther King did not march or die for this . . . King would be OUT- RAGED if he knew homosexualist extremists were abusing the Civil Rights Movement to get special rights based on their sexual behavior" (page 83). In a potentially milder example, I thought of how Kenyon may have used that image of Jackson and Ballard removed from the notion that they may have certainly experienced exclusion and ostracization while enrolled. Images are incredibly helpful tools to tell a story more completely, but potentially even more so to successfully enact an agenda which may mislead viewers. People are often trusting of images and their worth of a thousand words, which makes our jobs as new archivists and story-tellers all the more important. As we include names and faces, we are inherently using the image and legacy for our own means.

“African American Students Enrolled at Kenyon.” Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange, digital.kenyon.edu/archives-timeline/18/. Accessed 23 Mar. 2025.

Yazdiha. The Struggle for the People’s King. Princeton University Press, 2023.

Comments

Post a Comment