Forgetting the Battle at Blair Mountain

|

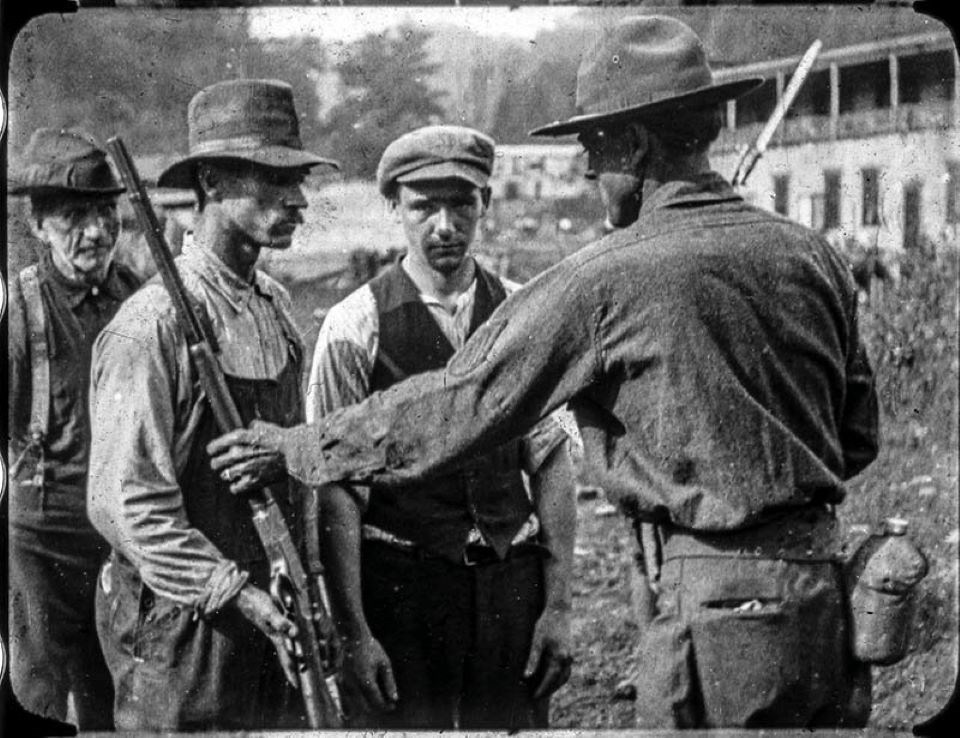

| Miners arm themselves are prepare to march (from U.S. NPS) |

On August 1st, 1921, Sid Hatfield, a West Virginia coal miner and local union hero, was gunned down by coal company agents in the shadow of the McDowell County courthouse. Hatfield was part of the effort to unionize the coal production of two areas, Mingo County and Logan County, both of which were controlled by staunchly anti-union coal operating associations. Following Hatfield’s murder, around 10,000 miners gathered in Marmet, West Virginia and, on August 24th, began marching towards Logan and Mingo. Having armed themselves, they intended to force an end to the use of “mine guards” in those counties. These agents, employed by the mines, were tasked with spying on miners, thwarting unionization efforts, and evicting striking miners from their (often company-owned) homes. Frustration with this violent arm of the mine owners boiled over when Hatfield was killed. At Blair Mountain, on the border between Boone and Logan Counties, the miners were met by over 2,000 Logan and Mingo County sheriff's deputies, state police, state militia, and mine guards. This force, many of whom had, for some time, been paid by the Logan County Coal Operators Association to put down unionization efforts, took position on the Blair Mountain ridge. They used machine-gun nests to fire down on the miners, and dropped gas canisters and homemade bombs from planes also hired by the Operators Association. On September 1st, the miners had captured half of the ridge, but President Warren Harding sent in federal troops to stamp out the violence. Perhaps because many of the union members were veterans of the first world war, they chose not to fight the U.S. Army and laid down their weapons. Just like that, the largest civil uprising since the civil war had ended. At least 16 miners lay dead, but no official count was ever taken (Robertson 2021)(Brown 2016).

The battle at Blair Mountain, a landmark event that demonstrates both the power of labor movements as well as our propensity to forget them, is a great event with which to analyze the commemoration of labor history in the U.S.. A useful way to begin thinking about commemoration and collective memory is with sociologist Eviatar Zerubavel’s piece “Social Memories: Steps towards a Sociology of the Past.”

In “Social Memories,” Zerubavel pushes back against what he calls a psychological conception of memory. Under this flawed understanding, he says, “the total lack of attention to the social context within which memory is actually situated supports a vision of "mnemonic Robinson Crusoes" whose memories are virtually free of any social influence or constraint” (Zerubavel 2011:221). Instead, Zerubavel argues for a view of memory that acknowledges the effect of society on what and how we remember. He calls this concept “mnemonic tradition.” As opposed to existing in a vacuum, one's personal memories are filtered through and entangled with the collective memory of those around them. There are a few ways the effects of “mnemonic tradition” are obvious, but it only becomes clear when we actively use this perspective. One main “mnemonic tradition” is what is taught in history class. Some have argued that the reason many people are not aware of the battle at Blair Mountain is that it has not been taught in k-12 history courses (Brown 2016)(Robertson 2021). It has seemingly been deemed unessential by the powers that control the mnemonic tradition in the classroom.

The important part of this process, then, is control over what is taught. Countless people decide what is put on countless history syllabi, of course, but by looking for the parties that have an incentive to keep this event out of the collective memory, we can begin to understand why so few are taught about a seemingly important historical event. In a 2021 New York Times article, Campbell Robertson argues that both sides of the conflict participated in this process. Those on the side of labor avoided talking about the incident, she writes, “out of self-protection and solidarity.” However, the side of industry, including the state, seems to have had a larger impact. Robertson says, “State officials demanded that any mention of Blair Mountain be stripped from federal oral histories. A 1931 state law regulated the “study of social problems” and for decades, the Mine Wars were left entirely out of school history textbooks. Today, the battlefield is owned in large part by coal operators, who until recently planned to strip mine Blair Mountain itself” (Robertson 2021:2). Zerubavel warns us of the power of this process. Once an official history has been encoded in oral histories and taught in schools, alternative memories of the past, like the Battle at Blair Mountain, become difficult to add to what is understood as legitimate and important history. However, there are efforts to commemorate the battle and the history of labor struggle in Appalachia more generally. This work has a crucial part to play in the ongoing fight to include labor history in our mnemonic tradition.

References

Brown, Richele C. 2016. “Power Line: Memory and the March on Blair Mountain.” Pp. 86-107 in Excavating Memory: Sites of Remembering and Forgetting, edited by M. T. Starzmann and J. R. Roby. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press.

Robertson, Campbell. 2021. “A Century Ago, Miners Fought in a Bloody Uprising. Few Know About It Today.” New York Times, September 6.

Zerubavel, Eviatar. 2011. “Social Memories: Steps towards a Sociology of the Past.” Pp. 221-224 in The Collective Memory Reader, edited by Jeffrey K. Olick, Vered Vinitzky-Seroussi, and Daniel Levy. Oxford University Press.

Comments

Post a Comment